A cost-of-living tax system

Taxes are an exercise in income redistribution that every society goes through. It's a way to level the paying field and invest in the public good. But the system we have in Canada is terribly over-complicated, with loopholes that favour the rich. When filing your taxes becomes so time-consuming that you need to buy special software or hire an accountant to do the job for you, it's high time for change. The complexity of the income tax system means that the only people who can navigate it effectively are those with time, money, or expertise to spare.

(There are similar issues with the corporate tax structure, but that's a whole different kettle of fish, so let's save it for another day.)

The fact is, paying taxes is one of the few responsibilities that we have as citizens. And like voting or jury duty, this should be something the average citizen is capable of doing on her own.

Tax incentives are a favourite tool among governments for offering all kinds of incentives, from the wildly popular home renovation tax credit, to the arts and sports tax credit, to the transit tax credit, to charitable donation tax receipts.

Part of the tax system's nebulousness is due to these kinds of exceptions and tax brackets meant to make taxation fairer. So how to strike that balance between fairness and simplicity? The Fraser Institute, among others, have advocated a flat tax, regardless of income, marital status, or number of dependents. That's simply too blunt an instrument. But there is a way to make taxation work better: tie it to the cost of living.

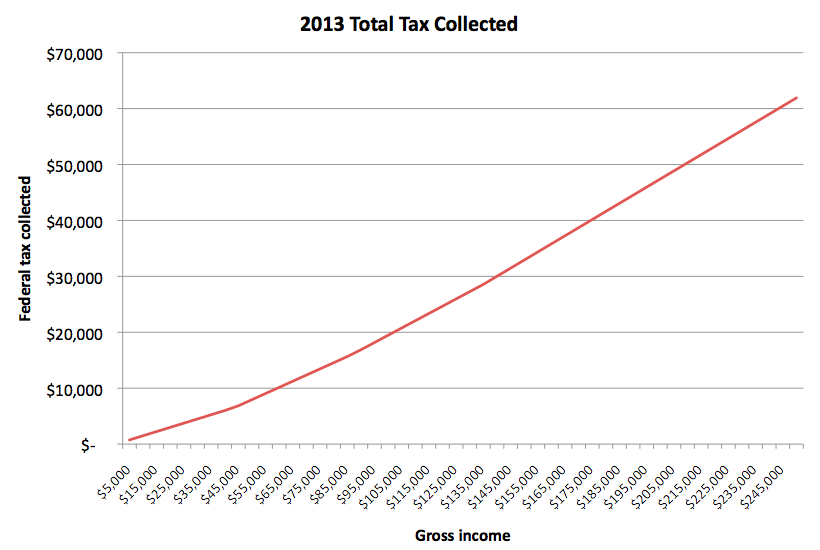

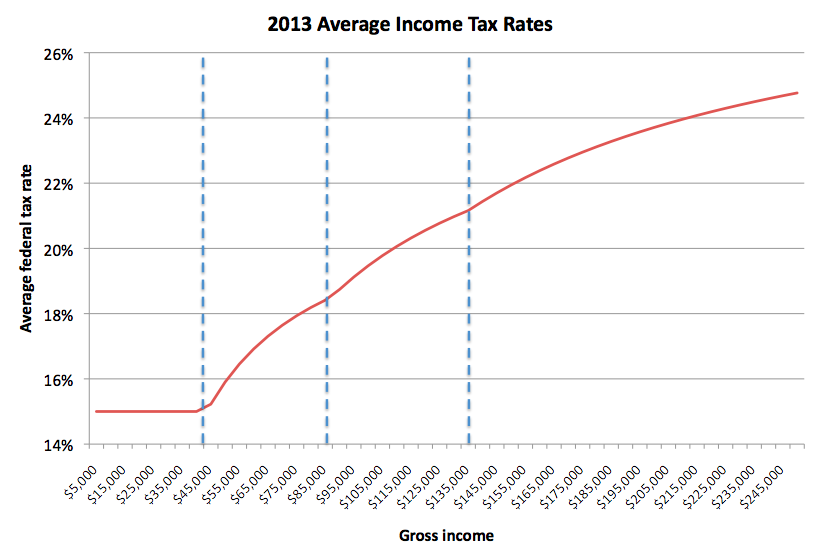

Before I dive in, let's take a look at the current federal tax system. Canada has four tax brackets (details here), and these charts show how much of your income is taxed depending on your gross earnings.

Now, what would tax rates look like if we accounted for cost of living? Statistics Canada keeps track of a Market Basket Measure (MBM), which fluctuates based on the cost of food, shelter, clothing, transportation, and other necessities to live modestly. The MBM differs depending on what province you live in and how large your community is.

For the sake of illustration, let's take a look at Toronto. Its MBM for 2010 was $33,177. In a hypothetical tax system based on cost of living, income below this threshold would not be taxed because we want everybody to afford at least a modest lifestyle.

The flipside of this issue is what is considered an extravagant income? I'm very much a believer in income ceilings, so I want my tax system to reflect that. A ceiling for some is necessary to provide a solid foundation for all.

With this in mind, let's lay out some tax brackets.

- Income lower than the MBM will be taxed at 0%

- Income between 1 and 2 times the MBM will be taxed at 15%

- Income between 2 and 3 times the MBM will be taxed at 20%

- Income between 3 and 4 times the MBM will be taxed at 25%

- Income between 4 and 5 times the MBM will be taxed at 30%

- Income over 5 times the MBM will be taxed at 90%

The tax rates are defined as multiples of the MBM, so that they reflect the actual cost of living. People in the top tax bracket are earning at least 5 times more than is required to live modestly.

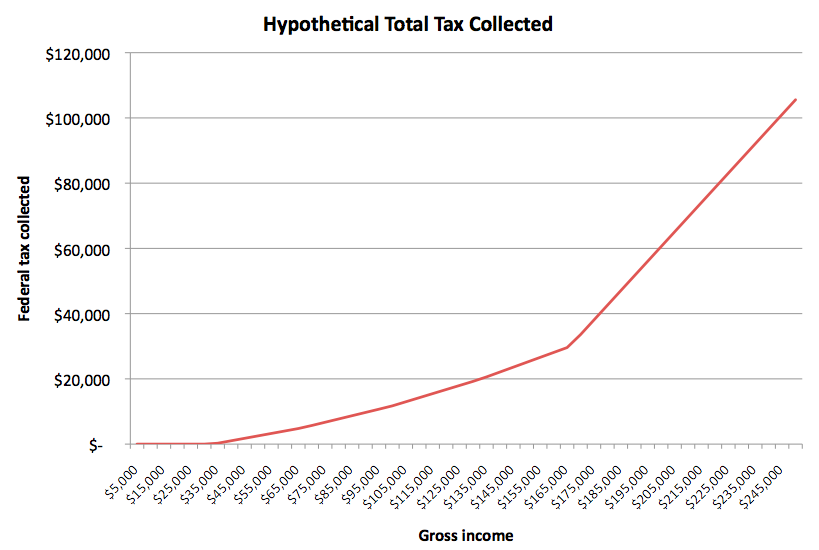

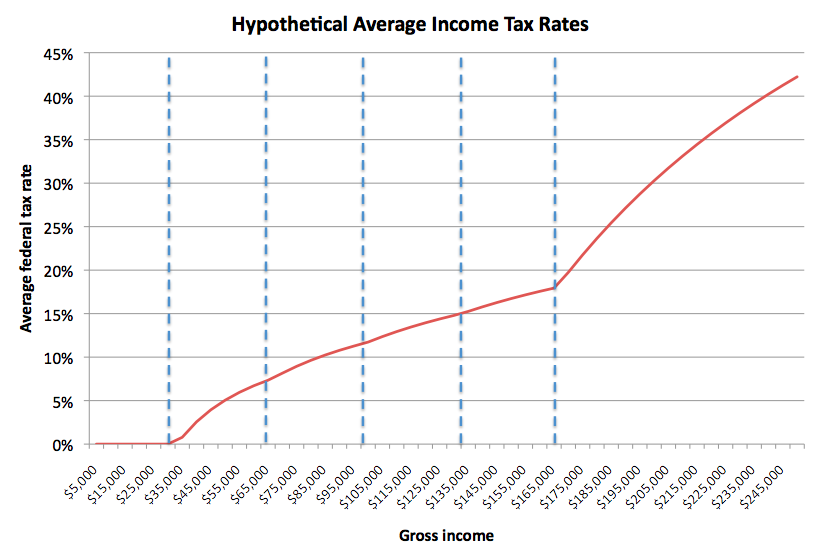

Let's take a look at the hypothetical average tax rates for Toronto under this system:

Let's circle back to what I was saying at the beginning of this post: our taxes are overcomplicated because of all the incentives that have been piled on by governments. This patchwork attempt to level the playing field and encourage certain behaviour has left us with a tax system that is too nebulous for regular people to take advantage of.

Tax brackets based on the MBM threshold would remove the need for some of those incentives - the transit tax credit and the northern living allowance, for example. Ideally, your income tax return would have only three questions: 1) your gross income; 2) your place of residence (so the MBM can be calculated); and 3) how many dependents you have.

As for other things not covered by the MBM, I'm of the opinion that the tax system is not the right place for them. Want to encourage post-secondary education? Lower tuition. Want to encourage kids' sports? Subsidize municipal athletic programs.

Taxes should be simple, transparent, and based on the cost of living. Is that too much to ask?

Sam Nabi