Take me to the beach: the long ride from Mexico to El Salvador

9 April 2016

La Libertad, El Salvador

We're sitting with a couple bottles of cheap beer at "La Ola 10", a restaurant in La Libertad, on El Salvador's Pacific Coast. It's been a trying three days, and we've decided to make for the beach, any beach, with waves and fish and sand and mariachi bands. Anything but the dry, dusty, mountainous trash heaps we've been traveling through for the past week.

As of now, we have everything but the sand. La Libertad's shore is full of large black rocks, the kind you could easily turn your ankle on if you try to walk across them too quickly. There are children playing in water, keeping to the shallows, waiting with glee for the waves to bowl them over. A young family sits on a rocky outcropping, close enough to the water's surface for the waves to give them a thorough soaking. But no one is properly swimming, whether because of the powerful sea current, or the rocky landscape, or all the detritus being thrown out from the fish market on the pier -- I'm not sure.

The fish market is a thing of quaint beauty. It starts from the boardwalk, continuing along the pier that juts out over the rocky beach, over the shallows, out about 300 metres to where it's deep enough to meet the fishing boats all coming in with their catch. The boats are hoisted, theatre-curtain style, laden with fish and shrimp and calamari. Some of the boats stay up on the pier, hawking their wares straight from the hull.

If you start from the tip of the pier and walk back to shore, the vessels are gradually replaced by market stalls. The open pier becomes covered. Raw whole seafood gives way to salted flanks of fish, fillets, de-tailed shrimp, and at the very end, abutting the boardwalk, a stall sells prepared mixed seafood, already cut up and ready to be used in the perfect salad. If you continue a few steps inland, you'll be accosted by a man selling knockoff Ray-Ban sunglasses.

This is the first place where I've felt a truly different culture since Monterrey. Granted, we didn't spend much time in the south of Mexico or Guatemala. Just enough time to have a healthy mixture of Pesos, Quetzales, and American Dollars (or rather, Salvadorean dolares) jingling around our pockets.

Also jingling around our heads for the past two or three days, like a handful of foreign currency, has been an incessant jarring headache. But let's back up. Back to San Cristóbal de las Casas…

7 April 2016

San Cristóbal de las Casas, Mexico

Our original travel plan through Mexico had us spending a night in Tuxtla Gutierrez, but multiple recommendations had convinced us to continue the extra two hours east to San Cristóbal. A smaller town, more friendly, more touristy, home to lots of authentic crafts and textiles from the south of Mexico. It was on our route anyway, so we decided to book a hostel with a nice view of the city, nestled between forested hills.

The town takes about an hour to walk end-to-end. It's big enough for a proper OCC intercity bus terminal, where we arrived after a twelve-hour ride from Mexico City. I spotted a yoga-aesthetic woman laden with a hiking backpack and two large duffel bags. Stepping out of the terminal and into the street, we brushed elbows with a straw-hat-wearing, guitar-toting hippie. Apparently, San Cristóbal has been a haven for backpackers and free spirits for at least 40 years. And they seem to be handling it well.

The downtown main street and labyrinthine artisan's market is the town's gringo trail, pulling in well-moneyed travelers like a vortex. People happily part with their cash to support the regional textile makers, coffee and chocolate producers, and all manner of handicrafts. This is the kind of shopping that doesn't seem to stink of consumerism so much. On the main street, you can still get two beers for 35 pesos, which is about as cheap as anywhere else we saw in Mexico.

San Cristóbal's central quarter has most anything us foreigners want — materially, culturally, and emotionally — and very few seem to venture further. This leaves the rest of the city open for laundromats, schools, dentist offices, vegetable stands, and restaurants for the locals.

As we walked around outside the downtown bubble, we came across almost exclusively local residents, apart from the group of European high school students touring the church, which has a magnificent view over the city.

We approached a group of women chatting along a tiny residential street, and discovered that it was a neighbourhood restaurant. They offered us breakfast, and made a delicious vegetarian meal for 30 pesos each — refried beans, cheese, eggs à la Mexicana, salad, tortillas, and coffee. These are not tourist prices. Not even semi-tourist prices. Excited, they asked to take our photo, and we posed awkwardly for four flashes of the smartphone camera.

San Cristóbal was the first city in Mexico we found with a culture of coffee-drinking. It was surprising how difficult it was to find a cup of coffee in Mexico City and Monterrey.

It was a beautiful little town, but we felt that one day of touring was enough and decided to leave the next morning. It would have been good to learn about the history of the Zapatistas – a revolutionary group that has roots in San Cristóbal, mounted a rebellion for indigenous rights, and has recently returned to speaking terms with the government. The local theatre regularly screens documentaries about the movement, but we didn't luck out – only Japanese anime and The Hateful Eight (dubbed into Spanish) would be screened that night. Alas, it was time for us to move on.

After consulting with the hostel, we decided not to travel with the GCC coach line to the Guatemalan border, as was our original plan. Instead, we booked a couple seats on a tourist shuttle that could take us directly to Guatemala City. The idea of being chauffeured across the border seemed nice, and the price was right at 700 pesos each. We got an early start, bags packed and waiting at 6:30 AM. We were told it would take 10 hours to reach Guatemala City. By 7:15, we were still waiting. This was the first indication of things to come.

Cuahuatemoc, Guatemala – Guatemala City

The shuttle eventually came. After half an hour, they shuffled us into a minibus, which took us to the border. We were made to get out and carry our bags through the small border village of Cuahuatemoc to the Guatemalan immigration office. Border formalities were relatively quick and painless — two dollars for the entry visa to Guatemala — but it took another hour for the minibus to come round and pick us up again. The reason we were made to wait around in the hot sun, as the bus driver kindly informed us, was that Guatemala hadn't switched over to daylight saving time yet. Clearly, we needed to wait for their clocks to catch up. Once an artificial hour (or rather, hour-and-a-half) had passed, we were ushered into yet another shuttle van.

It was becoming clear that we had been misled about the nature of this "tour company". There was no guide, no sightseeing, just a series of jumpy drivers barking out instructions. "Switch buses here for Lake Atitlán!", "Stay with me if you're headed to Guatemala City!" It seemed more like a semi-formal network of guys with vans, all overlapping and swapping passengers. The hostels that refer them are definitely getting a cut, as are the overpriced restaurants and convenience stores where we stopped along the way.

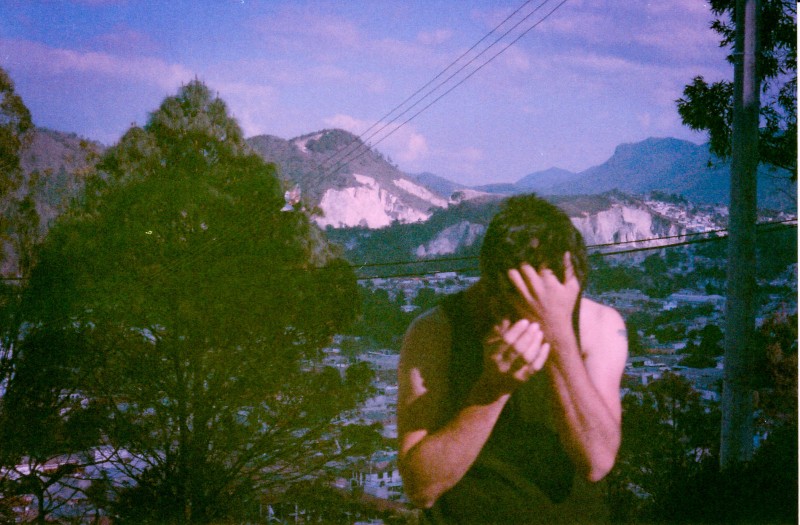

The route is full of detours, traffic jams and nausea – I blame the drivers in part, but the queasy roller-coaster of a ride was also due to the hilly Guatemalan landscape and the tiny, potholed, twisting roads that snake up and down and around its undulating valleys. Our headaches started early and persisted throughout the day. Guatemala did not impress us, to say the least.

The only way to deal with an excruciatingly long bus ride is to sink into a catatonic state. Pick a spot on the horizon and tune out until the buzz between your ears fades to a dull prodding. Indulge in your fellow passenger's word association game reluctantly, like a zombie. Meet the ripples of time as they come and let go quickly enough to prevent yourself from noticing how slowly the hours are crawling by. And by all means, don't look at your watch.

It's hard to stay Zen as the rough, hard-packed earth zips by you, front, back, and around. As the van swings about wildly, first swerving to pass a pick-up truck laden with labourers, now switching lanes to take the inside corner around a bend.

The constant jerking and jolting is all I really remember about our ride through Guatemala. When we finally reached Guatemala City, the van dropped us off inside the gated compound of a bus terminal, fronting onto a busy and unforgiving ring road.

Pedestrian crossovers would take us to the other side of the fast-moving expressway, where our options for dinner were gas-station packaged fare or Pizza Hut takeout. We got a large pineapple and cheese.

The gated compound is home to the bus terminal for TicaBus which would whisk us away in the morning, further south. We hadn't heard great things about safety in Guatemala City, we had no real desire to stay, and our goal had been to put as much distance behind us as possible. We figured we'd get a cheap hostel downtown, then wake up early to catch the bus. But we made two fatal miscalculations. One, that the TicaBus terminal would be remotely close to downtown, and two, that our "tour bus" from San Cristóbal would be remotely on time.

The only option at that point, at that hour of the night, was to take a room in the hotel adjacent to the bus terminal. That is, the hotel owned by the bus terminal, in the same compound as the bus terminal. It happened to be the same price as a taxi ride to downtown and back, and a reasonably priced hostel room. So, there we stayed with our cheese and pineapple pizza.

It was at this point, after a fourteen-hour rumble across mountainous terrain, after a twelve-hour coach ride the day before, that that creeping venom, doubt, burst to the fore.

Julia, always one to confront conflict head-on, broached the subject of our travel experiment. She mentioned the elephant in the room: flying back home from Colombia, or at best to Mexico. This would leave our experiment half-fulfilled, our convictions half-baked, our ambitions half-deflated, our environmentalist credibility half of what it was worth before we set out.

Because that's the whole point, right? To travel without the high greenhouse gas emissions of flying. To see far-off lands without killing the planet. And if we can't do that — actually do it as if planes didn't exist, then there's no hope. No hope for planes ever disappearing from the roster of passenger travel options. No hope of convenience ever being sacrificed for the greater good. No hope of a reversal of our car-centric cities, no hope of us ever electing a second Green MP.

All my effort, all my moral fibre rests on this trip remaining whole, indivisible, pure. Or so I thought, as I slipped into a teary funk, the kind caused by stress and not enough sleep and that takes just a pinch of existential doubt to set off.

So we slept. Next morning, we ate the rest of our cold pizza for breakfast and got on the bus to San Salvador, determined to take a break for a day or two. Above all, we wanted a beach.

9 April 2016

La Libertad, El Salvador

La Libertad is a place where you need to have your wits about you. Half a dozen cajoling men try to attract our business, like fishermen, as we search for a hotel along the beachfront promenade. Lonely Planet recommends Rick's, but Rick's is terrible. No ocean view, no outside facing window, bare-bones from floor to ceiling. No private bathroom. $25 per night.

We did better, scoring a $15 room in a concrete block of a building, painted the colours of an 80s high school gymnasium. It has a convenience store on the ground floor, a private toilet and shower in the room, a second-storey balcony lounge, ocean views, and wifi. It's only when we've already paid that we realize there's no running water at all, the wifi doesn't work, and we'll have to check out by 8:15 the next morning. Swindled!

As we saw upon arrival, the beach was rocky. A little further east of the town centre, however, the rocks dissipate somewhat and we see people properly swimming, surfing even. Just a few locals. No foreign tourists to be seen, other than a woman wearing a Secours Populaire Français t-shirt that I spotted around the fish market.

The sea is rough. Really rough. But we are excited for the ocean. We strip to our swimsuits and run out to meet the salty waves, only to be forced under backwards by Poseidon's chokehold. Barely able to stand before the next swell, we feel our feet pulled deeper as if by magnets, into the undertow.

The swirling water pulls along small and medium-sized rocks, which batter our toes and ankles. I lose my footing, falling forward as my knee makes contact with one of these rogue rocks strewn about the sand. The next waves come crashing in, toppling me head over heels. I somehow manage to protect my face.

Limbs full of scratches and bruises, mouths full of salt, we walk up to a beachside restaurant and order two Coca-Colas, Just like in the advertisements.

Beside us on the dark, rocky beach, two locals are fighting their dogs for fun. They snarl and snap, charge and growl. The two young men stand back and laugh.

Sam Nabi