Learning from 20 years of high-density development in Kitchener

When I have conversations with friends and neighbours about new housing being built in Kitchener, I see a strong sense of bewilderment — especially when they haven’t been downtown in a while.

“I don’t even recognize Kitchener anymore with all the new condo towers.”

“With these high-rises popping up all over town, we’re becoming like Toronto.”

I love this reaction because I’ve heard the exact same words delivered in a positive or negative light. “Becoming like Toronto” can mean someone’s excited for the influx of a young, diverse, metropolitan culture. Or it can mean they fear being packed in like sardines in a concrete jungle as the cost of living skyrockets.

Debate around new towers is a mainstay of our local media, and takes up a lot of the energy in the overall discussion on housing. The set-up is predictable by now: a builder wants permission to build more storeys than the city’s zoning rules allows, while immediate neighbours cry foul and get their photo taken in the newspaper, arms crossed and looking surly.

I call it "NIMBY Gothic" https://t.co/zoSTpjDl1P pic.twitter.com/3guN44S9o5

— TheBarnRazer (@BarnRazer) April 23, 2022

Clearly, some people in our community believe Kitchener is growing too fast. They see parallels to the rise of our city’s tech sector: the industry motto of "move fast and break things" seems to have seeped out from the software world into our housing market. There are valid criticisms that the surge in new high-rise development, especially downtown, isn't meeting residents’ needs. The towers, overwhelmingly 1-bedroom apartment units, cater to single high-income earners and real estate investors. Where’s the affordable housing? Where are the family-sized units?

This opposition to development sometimes gets characterized as the latest iteration of NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) sentiment. Established residents, typically living in single-detached homes on leafy tree-lined streets, oppose medium- and high-density projects of every size. Whether it’s a mid-rise infill project or a 44-storey tower on a disused parking lot, the objections still swirl with the same ferocity: not enough parking, too much traffic, too much shadowing, heritage preservation, neighbourhood character...

There will always be someone ready to explain why they support new housing, just not here. Or just not now. Or just not like this. Meanwhile, groups like WR YIMBY try to advocate for those future new neighbours who may live there one day.

Our perspective of Kitchener’s housing situation is distorted by the fact that we only need to have public meetings when someone asks for an exemptions to the zoning by-law. It’s a political process, too, since city council needs to make a decision at the end of the day. Could it be that we’re hyper-focused on a few widely-publicized fights, and the majority of developers are quietly following the rules and getting their building permits?

I decided to dig into these numbers by looking at all the building permits for 4-storey or taller buildings, from 2000 to 2021. Here’s a map!

Kitchener is growing fast…

Between 2016 and 2021, Kitchener's population grew by 23,663 people, or 10.1%. We’re the third-fastest-growing large city in Canada, just behind Brampton (10.6%) and Oakville (10.3%).

Making space for growth within our existing urban boundary is necessary. Infill housing, and high-density housing in particular, is key to ensuring we can grow in population without destroying our countryside, groundwater, and natural areas.

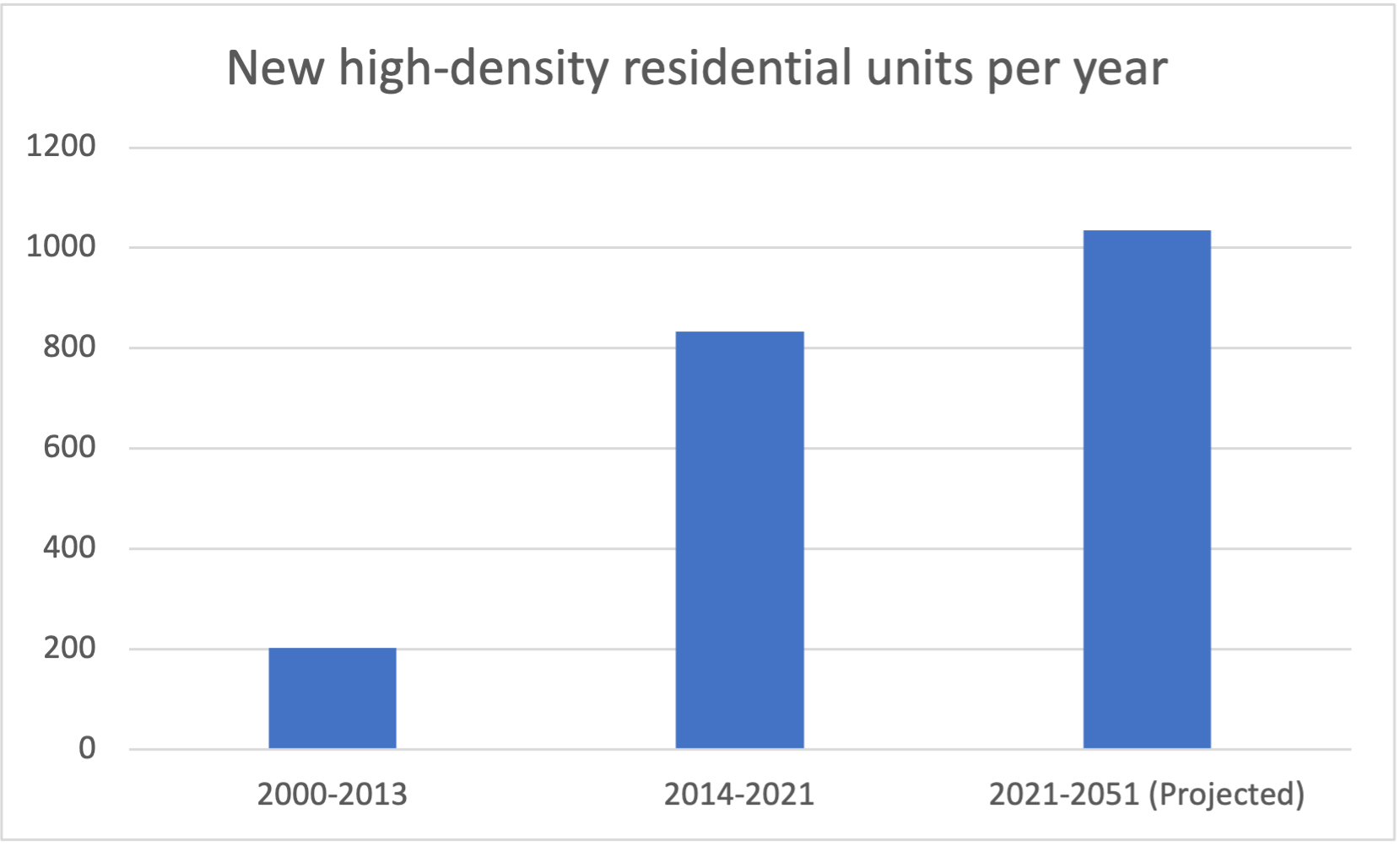

According to the Region of Waterloo’s draft Land Needs Assessment, Kitchener would need to accommodate 1,920 new residential units per year between 2021-2051 (Fig. 3-26), 54% of which should be in high-density buildings (Table 3-5). That means 1,036 new residential units per year in high-density buildings. (This is based on a growth scenario that doesn’t sprawl past our urban boundary.)

So, great! We have a target of 1,036 high-density units per year. How many have we been building? Are we on track to achieve that number?

… but not fast enough

I looked through Kitchener’s Open Data portal for all building permits for new construction of 4 storeys or taller. I consulted additional zoning details for each property to determine whether they got a by-law amendment or not, and asked city staff for help double-checking my spreadsheet (thanks Justin and Garrett!).

This left me with a list of 79 buildings across the entire city of Kitchener, which were built between 2000 and 2021.

Note: The definition of high-density in the Land Needs Assessment includes small apartments and stacked townhouses, so it doesn’t line up perfectly with the 4-storey cutoff that I used for building permit data.

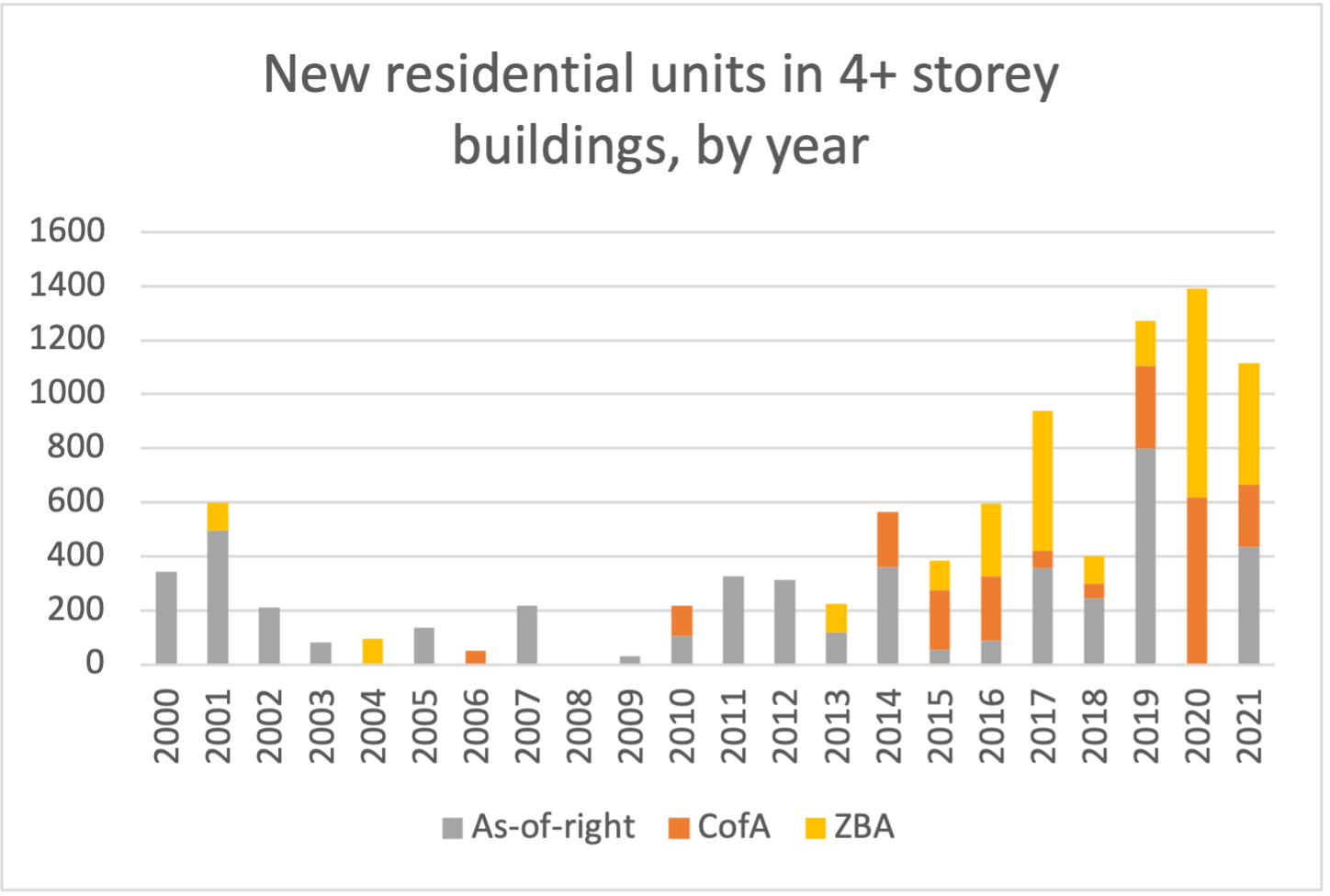

The timeline of development is interesting — there’s a clear increase in growth starting in 2014, and I’ll discuss why that year is important a little later on.

So: Between 2000-2013, we averaged 203 high-density units per year. From 2014-2021, we averaged 833 units per year. We need to keep up this pace, and even accelerate it, in order to build enough homes for everyone who needs one. Remember, we’re hoping to target 1,036 units per year going forward.

On the face of it, we’ve answered the question “is Kitchener growing too fast?” No! Not at all! We need even more high-density housing options, not less. If we put a moratorium on downtown development, or discourage medium- and high-rise buildings, we’ll push people out to far-flung subdivisions which are less affordable, less connected, and less financially viable for the city to service. We don’t want that.

Now that we know the number of high-density homes needs to keep increasing, we can ask ourselves: is the zoning by-law too much of a barrier? Is this why developers keep asking for amendments? Although it was recently rewritten, Kitchener’s zoning by-law had been out of date for many years.

If it’s true that Kitchener’s by-laws were woefully out of date for much of the past couple decades, we would expect to see many developments needing some kind of exemption — either a minor variance or a zoning by-law amendment.

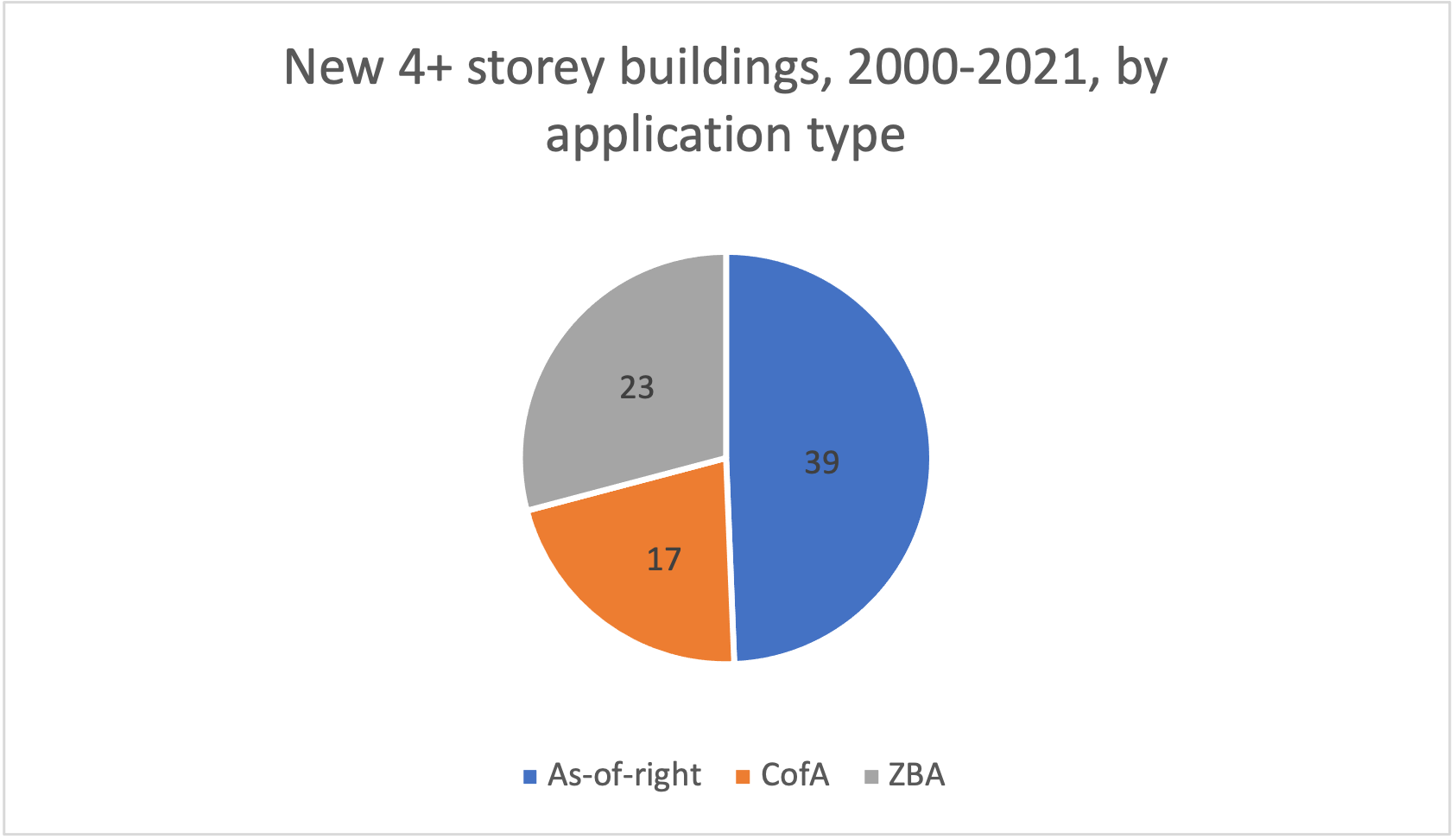

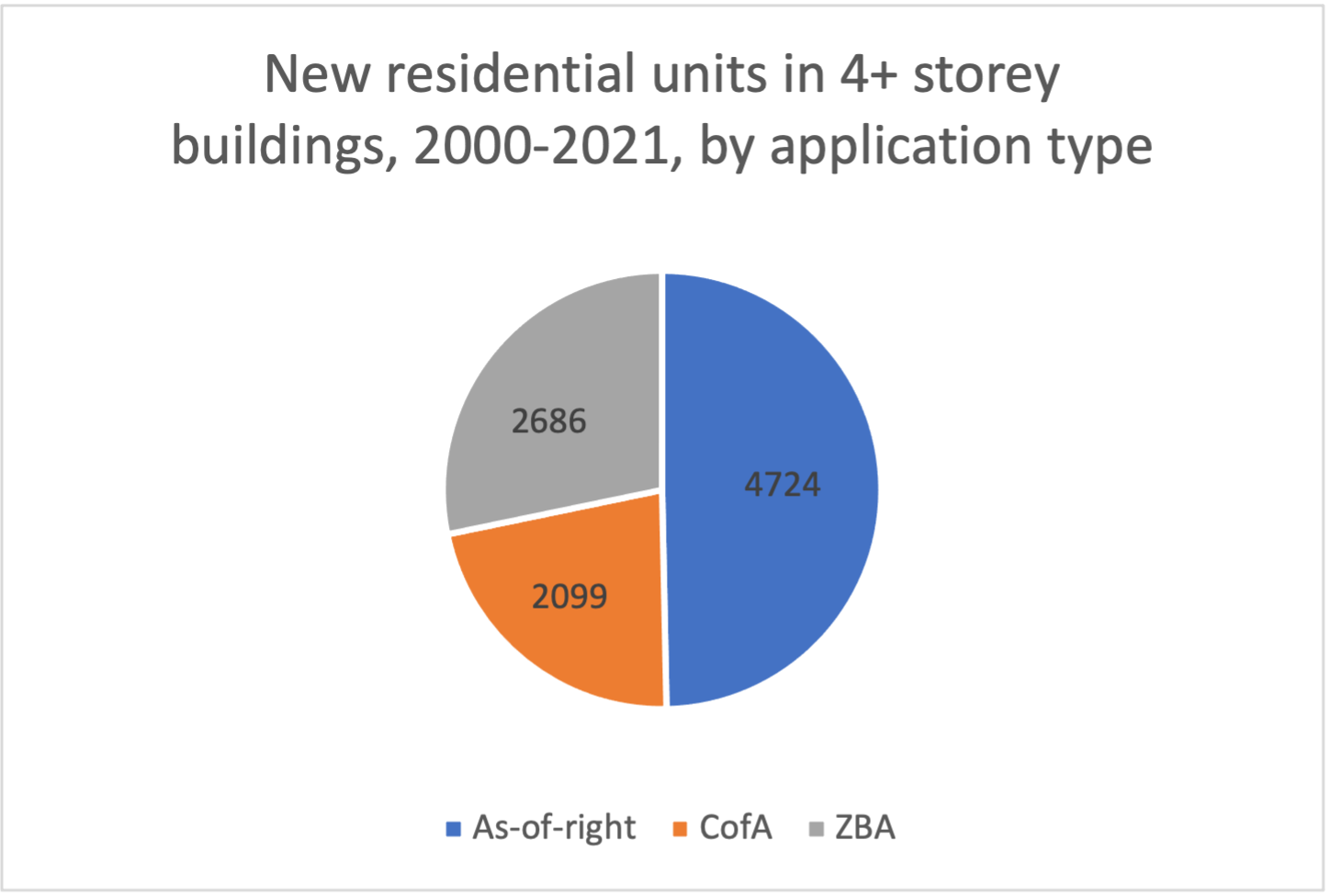

Looking through the building permits in my list, I was able to verify which ones were built as-of-right, which ones needed a minor variance approved by the Committee of Adjustment (CofA), and which ones needed a Zoning By-Law Amendment (ZBA) approved by city council. You’ll see these terms in the graphs below:

As-of-right: The building meets all zoning rules, and just needs a building permit.

CofA: The building got a minor variance, which costs a couple thousand dollars and takes a couple months to be reviewed by the Committee of Adjustment (a group of citizens appointed by council). The variance must be minor, appropriate for the area, and conform with the overall intent of the zoning by-law and official plan. (Usually, adding extra storeys is not considered minor.)

ZBA: The building got a zoning by-law amendment, which costs tens of thousands of dollars and takes six months or longer to be voted on by city council at a public meeting. It requires formal neighbourhood consultation and attracts more media coverage.

Half of all high-density buildings built from 2000 to 2021 were built as-of-right. This includes older slab-style apartments like The Regency at the corner of Queen St. and Weber St, but also new towers like Duke Tower Kitchener and Charlie West.

Roughly 22% of these buildings required a minor variance: some small detail that still met the overall intent of the zoning by-law, but

That leaves us with 28% of the buildings going through a full zoning by-law amendment, complete with public meetings and a council decision.

Looking at these building permits separated by year, we can see two distinct eras: between 2000-2013, 84% of buildings were built as-of-right. Between 2014-2021, that proportion was only 35%.

Downtown development charge waiver

From 2014-2019, Kitchener decided to waive development charges in the downtown core. That exemption was intended to spur growth, saving builders thousands of dollars per unit in fees. We did see a surge in new residential units. But we also saw a surge in minor variance applications and zoning by-law amendments.

So, did the development charge exemption free up developer budgets to apply for zone changes and add a few storeys to their projects? I think it played a part.

Of the 11 downtown developments that were issued a permit during 2014-2019, 5 got a zoning by-law amendment and 3 got a minor variance. Only 3 of them (Charlie West, 388 King St E, and 63 Scott St) were built as-of-right.

Looking ahead

We’re at a pivotal moment when it comes to how our city is planned. A lot of the rules and policies that have governed development are changing as we speak:

- Kitchener has just revamped its zoning-bylaw after 30 years

- Height & density bonusing (where developers enter one-off negotiations with the city for more storeys) is being phased out as we transition to Community Benefits Charges (a 4% fee for all tall buildings, not just those that seek zoning amendments)

- New housing policies in the Regional Official Plan will ensure affordability based on actual income levels, not only market rates

- The Regional Official Plan will allow more “missing middle” housing within neighbourhoods

- Inclusionary Zoning policies will mandate a percentage of housing in large developments near transit to be affordable

- City- and region-owned land will be made available for affordable and non-profit housing through the surplus land strategy

Each of these changes has the potential to help us transform from a fast-growing city, to a city that grows fast and equitably. We need to do a better job of welcoming new neighbours with various family sizes and at all income levels. We need to fund emergency shelters, supportive housing, and rent supplements for those experiencing housing insecurity. We need to make sure parks and open spaces keep pace with the influx of residents. We need a safe, connected network for bikes, e-scooters, skateboards, monowheels, and other mobility devices.

None of these goals will get achieved by discouraging new housing or putting a moratorium on development. Let’s make sure the next 20 years of growth does a better job at bringing everyone along for the ride: more diversity of unit sizes, more offerings at affordable rental rates, more co-op and non-profit housing, more missing middle housing and mixed-use neighbourhoods.

Thanks for reading! If you'd like to dig into the building permit data yourself, please feel free to download the Excel spreadsheet. Let me know what you do with it and let's continue the conversation.

Sam Nabi